A Plume of Bright Blue in Melissa’s Wake

Hurricane Melissa made landfall in Jamaica on October 28, 2025, as a category 5 storm, bringing sustained winds of 295 kilometers (185 miles) per hour and leaving a broad path of destruction on the island. The storm displaced tens of thousands of people, damaged or destroyed more than 100,000 structures, inflicted costly damage on farmland, and left the nation’s forests brown and battered.

Prior to landfall, in the waters south of the island, the hurricane created a large-scale natural oceanography experiment. Before encountering land and proceeding north, the monster storm crawled over the Caribbean Sea, churning up the water below. A couple of days later, a break in the clouds revealed what researchers believe could be a once-in-a-century event.

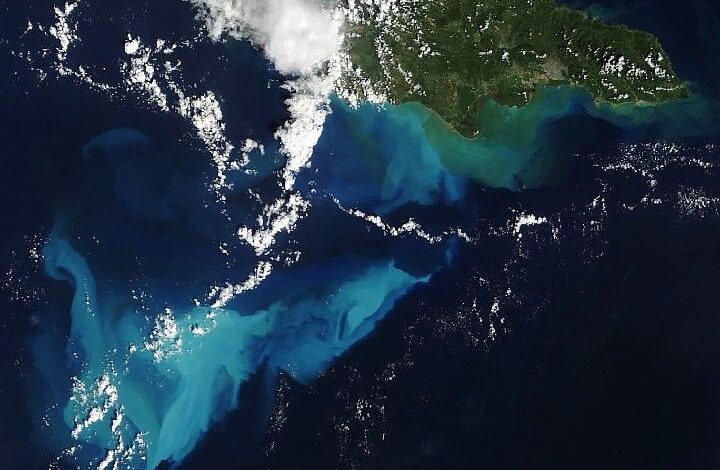

On October 30, 2025, the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) instrument on NASA’s Terra satellite acquired this image (right) of the waters south of Jamaica. Vast areas are colored bright blue by sediment stirred up from a carbonate platform called Pedro Bank. This plateau, submerged under about 25 meters (80 feet) of water, is slightly larger in area than the state of Delaware. For comparison, the left image was acquired by the same sensor on September 20, before the storm.

Pedro Bank is deep enough that it is only faintly visible in natural color satellite images most of the time. However, with enough disruption from hurricanes or strong cold fronts, its existence becomes more evident to satellites. Suspended calcium carbonate (CaCO3) mud, consisting primarily of remnants of marine organisms that live on the plateau, turns the water a Maya blue color. The appearance of this type of material contrasts with the greenish-brown color of sediment carried out to sea by swollen rivers on Jamaica’s southern coast.

As an intense storm that lingered in the vicinity of the bank, Hurricane Melissa generated “tremendous stirring power” in the water column, said James Acker, a data support scientist at the NASA Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center with a particular interest in these events. Hurricane Beryl caused some brightening around Pedro Bank in July 2024, “but nothing like this,” he said. “While we always have to acknowledge the human cost of a disaster, this is an extraordinary geophysical image.”

Sediment suspension was visible on Pedro and other nearby shallow banks, indicating that Melissa affected a total area of about 37,500 square kilometers—more than three times the area of Jamaica—on October 30, said sedimentologist Jude Wilber, who tracked the plume’s progression using multiple satellite sensors. Having studied carbonate sediment transport for decades, he believes the Pedro Bank event was the largest observed in the satellite era. “It was extraordinary to see the sediment dispersed over such a large area,” he said.

The sediment acted as a tracer, illuminating currents and eddies near the surface. Some extended into the flow field of the Caribbean Current heading west and north, while other patterns suggested the influence of Ekman transport, Wilber said. The scientists also noted complexities in the south-flowing plume, which divided into three parts after encountering several small reefs. Sinking sediment in the easternmost arm exhibited a cascading stair-step pattern.

Like in other resuspension events, the temporary coloration of the water faded after about seven days as sediment settled. But changes to Pedro Bank itself may be more long-lasting. “I suspect this hurricane was so strong that it produced what I would call a ‘wipe’ of the benthic ecosystem,” Wilber said. Seagrasses, algae, and other organisms living on and around the bank were likely decimated, and it is unknown how repopulation of the area will unfold.

Perhaps most consequentially for Earth’s oceans, however, is the effect of the sediment suspension event on the planet’s carbon cycle. Tropical cyclones are an important way for carbon in shallow-water marine sediments to reach deeper waters, where it can remain sequestered for the long term. At depth, carbonate sediments will also dissolve, another important process in the oceanic carbon system.

Near-continuous ocean observations by satellites have enabled greater understanding of these events and their carbon cycling. Acker and Wilber have worked on remote-sensing methods to quantify how much sediment reaches the deep ocean following the turbulence of tropical cyclones, including recently with Hurricane Ian over the West Florida Shelf. Now, hyperspectral observations from NASA’s PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem) mission, launched in February 2024, are poised to build on that progress, Acker said.

The phenomenon at Pedro Bank following Hurricane Melissa provided a singular opportunity to study this and other complex ocean processes—a large natural experiment that could not be accomplished any other way. Researchers will be further investigating a range of physical, geochemical, and biological aspects illuminated by this occurrence. As Wilber put it: “This event is a whole course in oceanography.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison, using MODIS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview, and ocean bathymetry data from the British Oceanographic Data Center’s General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO). Photo by Jude Wilber. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

- Acker, J.G. and Wilber, R.J. (2025) The first 25 years of satellite carbonate sedimentology: What have we learned? The Depositional Record, 11(3), 975-997. In: Kump, L.R., Ingalls, M., and Hine, A.C. (eds) Carbonate depositional environments: Past and future questions—A Tribute to the career of E.A. Shinn.

- Acker, J.G. and Wilber, R.J. (2024) Satellite-Derived Estimates of Suspended CaCO3 Mud Concentrations from the West Florida Shelf Induced by Hurricane Ian. Environmental Sciences Proceedings, 29(1):69.

- EBSCO Research Starters (2024) Carbonate Compensation Depths. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2025, November 25) A Direct Hit on Jamaican Forests. Accessed January 9, 2026.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2023, April 6) Stirring Up Carbonate in the Coral Sea. Accessed January 9, 2026.

Discover more from GTFyi.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.