Carbon Dating is Not Magic: A Simple Guide to How We Date Ancient Objects

If you’ve ever heard someone say carbon dating is guesswork or “just a lab trick,” here’s the reality: radiocarbon dating is a measured, testable method grounded in physics and cross-checked with real-world records. It doesn’t date dinosaurs or rocks millions of years old, and it’s not a black box. It’s a way to measure how long it’s been since something that was once alive stopped taking in carbon.

Also Read-What is Underwater Archaeology, and What Secrets is it Unlocking in 2025?

What we really measure.

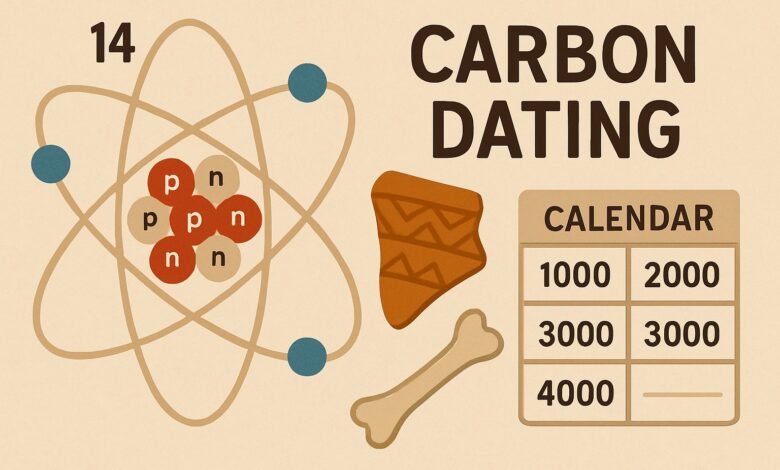

All living things absorb carbon. Most of it is the stable isotope carbon-12, with a tiny fraction as carbon-13 and an even tinier fraction as carbon-14. Carbon-14 (often written as 14C) is formed high in the atmosphere when cosmic rays hit nitrogen atoms, creating 14C that quickly becomes carbon dioxide. Plants take in this 14C through photosynthesis, and animals get it by eating plants or other animals. While an organism is alive, the ratio of 14C to 12C in its body tracks the atmosphere fairly closely.

When the organism dies, it stops exchanging carbon with the environment. From that moment, its 14C starts to decay at a predictable rate to nitrogen-14. That “clock” is what radiocarbon dating reads.

Half-life, without the jargon.

The key concept is the half-life—the time it takes for half of the 14C atoms in a sample to decay. For 14C, the half-life is about 5,730 years. After one half-life, 50% remains; after two, 25%; after three, 12.5%, and so on. The decay follows a simple exponential relationship: N(t) = N₀ e-λt, where λ = ln 2 / 5730 years.

Because the amount of 14C becomes vanishingly small after many half-lives, radiocarbon dating is most useful from a few hundred years old up to roughly 50,000–55,000 years with modern instruments.

From sample to date.

Radiocarbon dating is only as good as the sample and how it’s handled. Labs take care to remove contaminants—modern glues, conservation varnishes, humic acids from soil, or carbonates that could skew the result.

- Wood and charcoal often undergo an acid–alkali–acid wash to strip carbonates and humic acids.

- Bone is treated to extract collagen (the protein fraction) and may be ultrafiltered to isolate high-quality large molecules.

- Textiles, seeds, peat, and paper have tailored pretreatments; solvents can remove oils or pitches.

- Shells and carbonates are treated differently due to “reservoir effects” (more on that soon).

Once pretreated, labs measure the 14C/12C ratio. Two main methods exist:

| Method | How it works | Sample size | Typical use | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta counting | Counts radioactive decays over time | Large (grams of carbon) | Older studies, large samples | Slower; less sensitive |

| AMS (Accelerator Mass Spectrometry) | Counts atoms of 14C directly | Tiny (milligrams) | Modern standard | Faster; more precise; dates small or precious samples |

AMS is now the go-to for archaeology and forensics because it needs very little material and can deliver tighter uncertainties.

Why calibration matters.

The atmosphere’s 14C level hasn’t been perfectly constant. Solar activity, Earth’s magnetic field, volcanic emissions, fossil fuel burning (the “Suess effect”), and nuclear bomb tests all nudge the 14C baseline up or down. If you just fed the raw measurement into the decay equation, you’d get an “uncalibrated” radiocarbon age that can be off by decades to centuries.

To fix that, scientists match radiocarbon measurements to real-world records with known calendar ages—most famously tree rings (dendrochronology), but also layers in lakes (varves), corals, and cave formations. These datasets are combined into calibration curves, such as IntCal, which labs use to convert a radiocarbon age into a calendar age range, usually reported with a probability (for example, 95% confidence).

Two related details to keep in mind:

- Labs report ages as years “BP” (Before Present), where “Present” is defined as 1950.

- Measurements are corrected for natural isotope fractionation using δ13C, so materials with different biochemistry can be compared fairly.

What carbon dating can date.

Radiocarbon dating works on things that were once alive, or on materials that contain carbon from living things.

- Wood, charcoal, bark, twigs, seeds, and plant fibers

- Bone and antler (via collagen)

- Peat, paper, textiles, parchment, leather

- Charred food residues on pottery

- Shells and carbonates (with reservoir cautions)

- Soot and soot-bound organics

- Modern organics for “bomb-pulse” dating (post-1950)

It does not date metals, pure stone tools, or volcanic rocks directly. You can often date the soot on a hearth, the collagen in a bone, or the charred residue on a pot, but not the granite itself.

Time range and precision.

With AMS, the practical upper limit is around 50,000–55,000 years. Precision depends on sample size, preservation, and the calibration curve’s shape at that time period. In historical times, uncertainties can be a few decades; far back in the Late Pleistocene, typical uncertainties can be several hundred years or more. Results are reported as calibrated ranges (often multiple possible windows if the calibration curve “wiggles” there).

What can trip it up.

Radiocarbon dating is robust, but it’s not foolproof. Common pitfalls include:

- Contamination: Modern carbon makes samples look younger; ancient “old” carbon (for example, limestone dust) can make them look older.

- Reservoir effects: Marine organisms often look several hundred years “too old” because deep ocean water contains dissolved ancient carbon. Some lakes and rivers have a freshwater reservoir effect (the “hard-water effect”), which can make shells or snails appear much older than they are.

- Old wood problem: A timber used in a structure might be centuries older than the building if it came from the heartwood of a long-lived tree or was reused.

- Context mix-ups: Charcoal can drift between layers; bioturbation (burrowing) can move small items.

- Very recent samples: Post-1950 materials are best dated with the “bomb spike” (dramatic rise in 14C from nuclear testing peaking around 1963–64) rather than classic pre-1950 calibrations.

Good labs lean on careful pretreatment, control samples, and multiple lines of evidence from the site to minimize these issues.

Real examples you’ve heard of.

- Ötzi the Iceman: The mummified body found in the Alps in 1991 was dated by several labs to the Copper Age, around 3350–3100 BCE, aligning with tools and clothing found with him.

- Dead Sea Scrolls: Fragments tested by radiocarbon cluster in the last centuries BCE to the first century CE, consistent with paleographic dating.

- Shroud of Turin: In 1988, three labs independently dated samples to roughly 1260–1390 CE, indicating a medieval origin for the linen. Debates continue, but the multi-lab result remains a landmark.

- Post-bomb forensics: The spike in atmospheric 14C after 1950 lets scientists date modern materials within a decade or so—used to detect illegal ivory, authenticate wine vintages, and check the “age” of cells in medical research.

How labs report results.

Expect to see:

- An uncalibrated radiocarbon age in years BP with an uncertainty (for example, 2480 ± 30 BP).

- A δ13C value used for fractionation correction.

- One or more calibrated calendar age ranges with probabilities (for example, 760–410 BCE at 95% probability), derived from the current calibration curve.

- Notes on pretreatment steps and sample quality.

Multiple ranges can appear because the calibration curve is not a straight line—its wiggles can map one radiocarbon age to more than one calendar interval. Archaeologists narrow this with site context and other dating methods.

A quick refresher on isotopes.

An isotope is simply an atom of the same element with a different number of neutrons. Carbon-12 and carbon-13 are stable; carbon-14 is radioactive. Because 14C is so rare and decays over time, its changing ratio to 12C is the “signal” radiocarbon dating reads. The physics is universal; the pattern of 14C in the atmosphere is what needs calibration.

Why it’s trustworthy.

Radiocarbon dating didn’t appear from nowhere. Willard F. Libby and collaborators developed it in the late 1940s and validated it by testing objects of known age—from Egyptian artifacts with historical dates to tree rings with exact counts. Libby received the 1960 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work. Since then, the method has been refined with better detectors (AMS), better chemistry (pretreatments), and better calibration datasets (notably long tree-ring sequences from bristlecone pines and European oaks). Independent lines of evidence—stratigraphy, dendrochronology, ice cores—regularly agree with radiocarbon within expected uncertainties.

Common misconceptions.

- “It can date anything.” It only dates once-living materials or carbonates that interacted with the atmosphere or oceans.

- “It works on millions of years.” Beyond about 50,000 years, there’s too little 14C left to measure reliably.

- “One date tells you everything.” Context matters: what material was dated, from where in the site, and how it was treated.

- “All sea shells are fine.” Marine and some freshwater shells often need reservoir corrections; sometimes they’re not the best choice.

Good practice in the field.

- Choose the right material: short-lived plants or seeds are better than long-lived wood when dating an event.

- Keep it clean: avoid consolidants, glues, and handling contamination; document any conservation history.

- Date multiple items: independent samples converge on the most likely time frame.

- Combine methods: use radiocarbon with stratigraphy, typology, and other absolute methods for a secure chronology.

Bringing it together.

Carbon dating isn’t magic, and it isn’t guesswork. It’s a way to measure time from the physics of radioactive decay, carefully corrected to the real atmosphere’s history and applied to the right materials. When you see a date on a museum label or in a paper, you’re looking at the end result of chemistry, counting atoms, and cross-checking against living records like tree rings. That’s why radiocarbon dating remains one of archaeology’s most powerful tools—and why its strengths and limits are both well understood.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and aims to provide a clear understanding of the radiocarbon dating process based on current scientific knowledge. It should not be used as a sole resource for detailed scientific research or in professional archaeological or forensic contexts. Always consult specialized literature and certified laboratories for specific dating needs.

Discover more from GTFyi.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.