10 Deadliest Cosmic Rays in the Universe

On September 1–2, 1859, the Carrington Event produced aurora visible at tropical latitudes and disrupted telegraph systems worldwide. It remains the classic example of a solar-driven particle storm.

Fast-forward to 1991: a single cosmic ray dubbed the “Oh-My-God” particle carried roughly 3×10^20 electronvolts, a reminder that individual particles sometimes pack enormous power.

Some cosmic particles are mostly harmless curiosities; others deliver energies or damage mechanisms that make them the most biologically and technologically damaging in the universe. High linear energy transfer (LET), deep penetration through shielding, and enormous energy per particle are the usual reasons scientists label a particle “deadly.”

This piece ranks the 10 deadliest varieties, explaining their physical properties, notable observations, real-world impacts on astronauts, satellites and aircraft crews, and where researchers study them. The list is grouped into heavy ions, common high-energy particles, transient/ultra‑high‑energy events, and secondary/exotic hazards.

Heavy nuclei and high-Z particles

High atomic-number (Z) cosmic-ray nuclei deposit energy very densely along their tracks, producing high linear energy transfer (LET) that makes a single traverse much more damaging than a comparable proton hit. That dense ionization produces clustered DNA damage, complex chromosomal breaks, and greater difficulty for cellular repair mechanisms.

Heavy ions are far less common than protons—only a few percent of galactic cosmic rays by number—but they account for a disproportionate fraction of biological risk per particle. They also punch through conventional shielding differently, creating secondary cascades that complicate protection for astronauts and microelectronics.

Instruments such as AMS‑02 on the International Space Station, ACE at L1, and the Voyager probes measure composition and flux of heavy nuclei. Laboratory heavy‑ion accelerators (for example, the NASA Space Radiation Laboratory) simulate these particles for biological and electronics testing.

For deep‑space missions beyond low Earth orbit—Moon and Mars missions—high‑Z ions are a primary concern because mass-based shielding becomes inefficient: thicker material reduces some doses but increases secondary production for energetic heavy ions, so designers balance mass, materials, and active monitoring.

1. Iron nuclei (Fe) — the most damaging heavy ions

Iron nuclei (Z=26) are among the most biologically damaging components of galactic cosmic rays because their charge and mass create very dense ionization tracks. Even a single iron ion at typical GCR energies can produce complex, clustered DNA damage that is hard for cells to repair.

Composition measurements show heavy nuclei are a few percent of GCRs by number, with iron among the dominant heavy species. Typical iron energies range from ~100 MeV per nucleon to many GeV per nucleon in galactic cosmic rays; even a 1 GeV/nucleon iron ion carries substantial LET.

Shielding against iron is challenging: dense material reduces particle range but amplifies secondary fragmentation and neutrons. NASA’s Space Radiation Laboratory performs heavy‑ion tests to characterize biological effects and verify shielding concepts for astronauts on missions beyond low Earth orbit.

2. Silicon and oxygen nuclei — common heavy hitters

Silicon and oxygen are mid‑Z ions that appear relatively frequently among heavy cosmic-ray nuclei and deliver serious damage per hit. Oxygen is particularly abundant in cosmic-ray composition studies, with silicon also prominent among the mid‑Z group.

Although each Si or O ion is less damaging than iron on a per‑particle basis, their higher abundance means they represent a steady hazard. For electronics, mid‑Z ions increase single‑event effects: bit flips, latchups, and permanent damage in microelectronics.

Satellite anomalies and ground testing trace many single‑event upsets to mid‑Z ion strikes. Facilities that fire silicon and oxygen beams at chips and materials provide the data manufacturers use to harden spacecraft electronics.

3. Alpha particles (helium nuclei) — frequent and damaging in numbers

Alpha particles (helium nuclei) are the second‑most common component of galactic cosmic rays after protons, comprising roughly 10% of the flux by number. Their LET is moderate but, because they are common, they contribute substantially to cumulative dose.

Typical helium energies span tens of MeV per nucleon up to several GeV per nucleon. At aircraft altitudes and in space, cumulative exposure from alphas contributes to dose accumulation for crew and passengers on long or frequent flights.

Radiation risk models for Moon and Mars missions explicitly include the helium flux; measured dose increases at flight altitudes confirm that alphas are part of the background that airline crew accumulate over careers.

High-energy protons and leptons

Protons dominate cosmic-ray flux by number and drive much of the cumulative radiation dose in near‑Earth space. Electrons and positrons are fewer but create secondary photons and Bremsstrahlung when they slow, producing additional hazards inside shielding.

When protons or leptons hit shielding or the atmosphere, they produce showers of secondary particles—neutrons, muons, and gamma rays—that often determine internal dose distributions. Spacecraft and aircraft systems must account for these indirect effects as well as the primaries.

Detection and monitoring platforms such as ACE, Voyager, and the Parker Solar Probe, plus instruments like AMS‑02, provide flux and composition data that feed operational forecasts and design standards for electronics and crew protection.

4. High-energy protons — the most common threat

Protons make up roughly 90% of cosmic-ray particles and are central to radiation exposure calculations in space. Typical energies range from tens of MeV to many GeV, with solar energetic particle (SEP) events producing intense bursts of lower‑energy protons.

Solar events can spike proton flux by orders of magnitude in minutes to hours. The October 1989 storm caused widespread satellite problems and is a useful operational benchmark; in extreme historical cases like the 1859 Carrington Event, ground systems and aurora extended to low latitudes.

Operational responses on spacecraft focus on proton protection: storm shelters on the ISS, real‑time monitoring, and conservative mission planning. Proton shielding reduces acute dose but must balance mass and secondary production when design constraints are tight.

5. Electrons and positrons — penetrating and electrically disruptive

Relativistic electrons and positrons are less numerous than protons but can generate penetrating secondary X‑rays and Bremsstrahlung when decelerated. They play an outsized role in spacecraft surface charging and in creating internal photon doses.

The Van Allen radiation belts concentrate energetic electrons that cause surface charging and arcing on satellites. AMS‑02 measurements of positron excesses also inform astrophysical models and sometimes point to energetic sources that contribute to local particle environments.

Designers mitigate electron effects with conductive coatings, grounding strategies, and localized shielding; nevertheless, secondary photons from electrons can increase dose to sensitive electronics and to crew in poorly shielded areas.

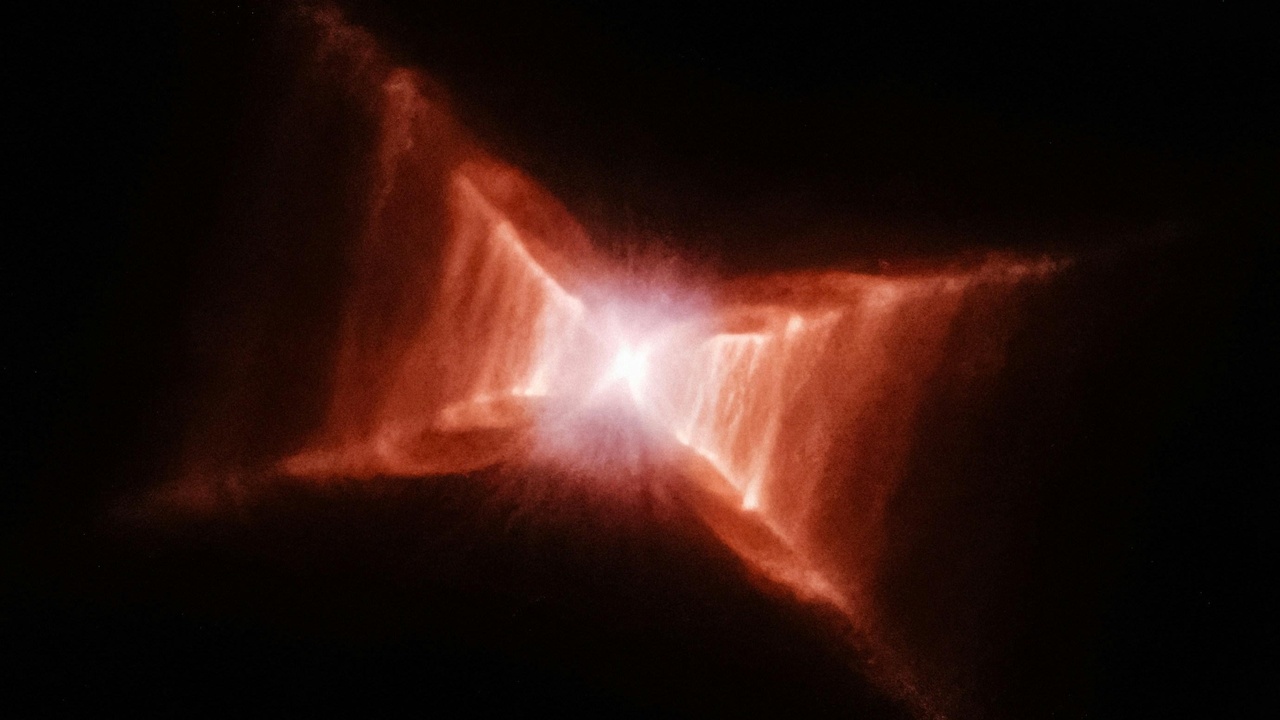

Ultra-high-energy and transient cosmic rays

Transient astrophysical events and ultra‑high‑energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) produce the most energetic individual particles we know of. Energies exceed 10^18 eV and can reach beyond 10^20 eV, with rare particles that pack as much kinetic energy as a baseball pitch into a single subatomic particle.

Although extremely rare, these particles create massive air showers when they strike an atmosphere, producing cascades of secondary particles that can affect atmospheric chemistry locally and generate detectable footprints across large ground arrays.

Observatories such as the Pierre Auger Observatory and the Fly’s Eye/HiRes experiments track UHECRs, while neutrino detectors like IceCube search for complementary high‑energy messengers from the same catastrophic sources.

6. Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) — single particles with enormous energy

By definition, UHECRs carry energies above ~10^18 eV, with the most famous example being the 1991 “Oh‑My‑God” particle at about 3×10^20 eV. At the highest energies the flux is tiny—roughly 1 particle per km2 per century—yet each arrival produces an extensive air shower that spans many kilometers.

Pierre Auger and other large arrays detect these showers via surface detectors and fluorescence telescopes. The cascades produce millions or billions of secondary particles, including muons and neutrons, giving insight into source properties and into particle interactions at energies beyond terrestrial accelerators.

UHECRs are primarily an astrophysical concern: they help us study extreme accelerators and magnetic fields. Locally, the chance a UHECR causes harm is negligible, but their existence underscores the energy scales nature can reach in single particles.

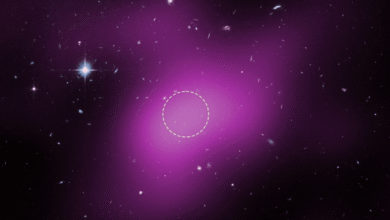

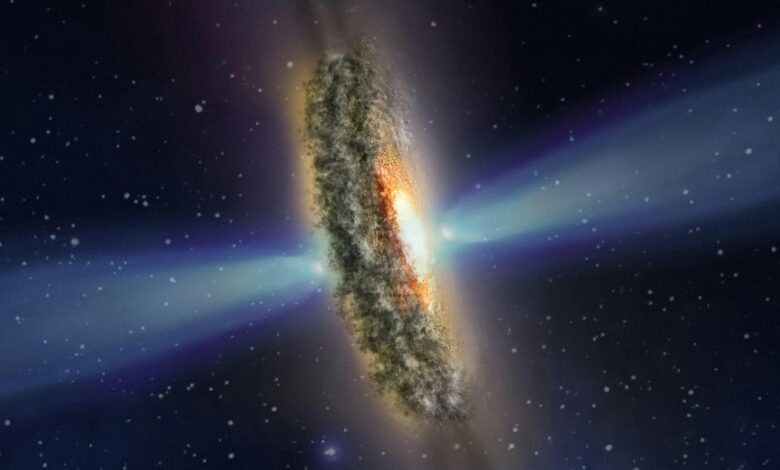

7. Gamma-ray burst (GRB) photons and associated particles

Gamma‑ray bursts release enormous photon and particle energies in seconds to minutes. Isotropic‑equivalent energies can reach ~10^44–10^47 joules, and a nearby GRB pointed at Earth could significantly alter atmospheric chemistry, producing ozone depletion and nitric oxides.

Rates of dangerous, nearby GRBs are very low—perhaps a few per galaxy per million years—but their potential biospheric effects made them a candidate in some mass‑extinction hypotheses. Swift and Fermi provide continuous monitoring of GRBs and constrain local risk by cataloging distances and energetics.

While a nearby GRB is improbable, scientists include GRB scenarios in planetary habitability studies and in assessments of long‑term biospheric hazards for Earth and exoplanets.

8. Solar energetic particle events (SEPs) — intense but local hazards

Solar energetic particles—protons and heavier ions accelerated by flares and coronal mass ejections—produce the largest short‑term increases in particle flux near Earth. SEPs can raise dose rates by orders of magnitude for hours to days.

Historical examples include the 1859 Carrington Event (aurora and telegraph disruption) and the October 1989 solar storms that damaged satellites and power systems. For astronauts, an unshielded exposure during a strong SEP can deliver an acute dose that requires immediate sheltering.

NOAA and NASA operate space weather forecasting centers (NOAA/SWPC and NASA models) that provide warnings and operational guidance; the ISS has storm shelters and procedures to reduce SEP risk during extravehicular activities.

Secondary cascades and exotic penetrators

Often the most damaging effects occur not from the primary particle but from the secondary cascade that follows when primaries strike atmosphere or shielding. Neutrons and muons can penetrate deeply into structures and tissues, while neutrinos pass through almost everything.

Secondary particles can increase dose inside a spacecraft or aircraft cabin and can induce radioactivity in materials. Designers must consider both primary stopping power and the spectrum of secondaries produced by candidate shielding materials.

Instruments such as neutron monitors, muon detectors, IceCube for neutrinos, and ground arrays quantify these secondaries and inform safety models for aviation, spaceflight, and ground infrastructure.

9. Secondary neutrons and muons — hidden, penetrating threats

When primaries strike the atmosphere, they spawn cascades rich in neutrons and muons capable of penetrating into buildings and aircraft. Muon flux at sea level is roughly ~1 per cm2 per minute; neutron fluxes are lower but contribute importantly to dose and to single‑event effects in electronics.

At typical cruise altitudes, aircraft crews see higher doses because they ride closer to the cascade source; polar routes amplify exposure due to geomagnetic cutoff effects. Neutron‑induced single‑event upsets have been recorded in avionics and in ground systems.

Shielding that blocks primaries without accounting for secondaries can make matters worse, so materials research and careful simulation are essential for effective protection strategies in aviation and spacecraft design.

10. High-energy neutrinos and antimatter — rare but information-rich

Neutrinos are nearly non‑interacting, so they don’t deliver direct dose in practical terms; however, high‑energy neutrinos are valuable messengers of catastrophic astrophysical sources. IceCube’s detection of PeV neutrinos (2013) opened a new window on extreme accelerators.

Antimatter particles—antiprotons and positrons—arrive as a small component of cosmic rays and can produce hazardous secondaries when they annihilate in shielding or tissue. AMS‑02 measures antiproton and positron spectra to study propagation and potential exotic sources.

Both neutrinos and antimatter are rare relative to protons and heavy ions, but they provide crucial situational awareness. High‑energy neutrino alerts can flag extreme events that merit follow‑up, while antimatter signatures help refine models of cosmic‑ray origins.

Summary

- Heavy ions like iron deliver outsized biological damage per particle and are a central deep‑space concern.

- Protons dominate flux while SEPs produce the largest short‑term spikes (Carrington Event 1859; October 1989).

- UHECRs (e.g., the 1991 “Oh‑My‑God” particle at ~3×10^20 eV) and GRBs are rare but carry catastrophic potential in special cases.

- Secondary particles—muons (~1/cm2/min at sea level) and neutrons—often produce the most penetrating effects inside structures and aircraft.

- Ongoing monitoring (Pierre Auger, AMS‑02, IceCube, NOAA/SWPC) and improved shielding research remain vital to manage the deadliest cosmic rays and protect astronauts, satellites, and aviation crews.

Enjoyed this article?

Get daily 10-minute PDFs about astronomy to read before bed!

Sign up for our upcoming micro-learning service where you will learn something new about space and beyond every day while winding down.

Discover more from GTFyi.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.